In the McMillen household, our traditional Easter meal was brunch, highlighted by a tremendous dish my father made, with layers of eggs and salt pork. Since Dad died, my brother Greg has taken on the responsibility, and what a wonderful job he does. This year, I (Anne) also made it here in St. Croix, along with baked beans (unfortunately canned, at home we used to make homemade in a real bean pot) and coffee cake. Friends brought fried potatoes, fruit salad (you've got to have something healthy!), and champagne and orange juice for mimosas. What a feast we had. Then I spoke with my family gathered at Greg's house, who were eating much the same menu. You know, new has its place, but there's also a lot to be said for tradition.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Friday, March 29, 2013

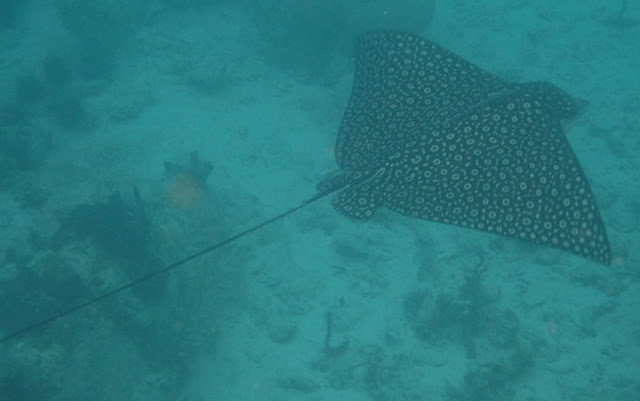

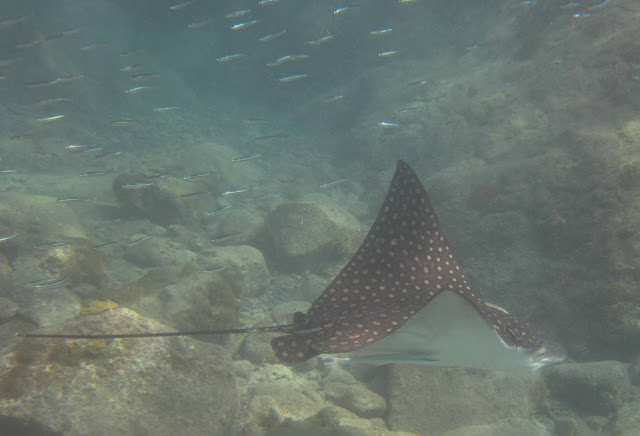

Creature Feature: Spotted Eagle Ray

| |

| Look at how long the tail is compared with the body |

Spotted eagle rays—what a beautiful and impressive sight when you’re underwater. With wingspans of to eight feet or more, you never miss seeing them when they’re passing, trailed by a slender tail that’s more than twice as long as the length of the ray’s body. They’re not usually shy (unless you chase them with a camera), swimming right by or under you. They feed on mollusks, and we’ve watched them snuff through sand or seagrass in search of a meal, accompanied by fish that dart in to pick off any little critters that the ray stirs up. Like sharks, spotted eagle rays often have remoras or sharksuckers hanging off of them. Also like sharks, rays have cartilage rather than bones, which contributes to their flexibility and makes them so graceful in their movement, it’s like they’re flying through the water when they slowly flap their great wings. Though many rays are a rather bland gray, spotted eagle rays on top are dark brown with beige or white markings—lines, circles, arcs—in fantastic patterns, and bright white below. Just beautiful!

|

| Beautiful color patterns on this spotted eagle ray that we sighted at St. John, USVI |

|

| Spotted eagle ray with a shark sucker on its white underside |

Friday, March 15, 2013

Creature Feature: Humpback Whales

| Not very exciting picture, but this is the knuckle one of the whales left in the water beside Mr Mac. Note that I'm looking down, not out into the distance. These whales were close! |

|

| Humpback calf checking us out (that's our outboard engine on the right) |

| Humpback mother and calf off of Guadaloupe |

Monday, March 4, 2013

Undersea Science

We were snorkeling off at Beehive Cove, which is off of Great

Lamshur Bay, St. John, USVI, and saw these objects fixed underwater, obviously

part of someone’s experiments. The plates could be to determine settlement

rates of sessile reef invertebrates, like corals, sponges, stuff like that. A

friend in grad school with Anne in Galveston did a similar experiment to

determine the settlement rate of barnacles, something that’s close to cruiser’s

minds, if not exactly near and dear to their hearts. The tubes could be

sediment traps to determine the rate or extend of sediment deposit. Then again,

I could be completely wrong and they could be something else entirely!

Labels:

Caribbean,

Underwater

Friday, March 1, 2013

Creature Feature: Jellyfish

|

| The pink circles are the reproductive organs of this moon jelly |

|

| Moon jelly pulsing - see the fringe of tentacles around the bell? |

Jellyfish. What can you say – they’re beautiful balls of

mucous. Living on a boat and snorkeling, as we do, you see a lot of jellyfish. As

cnidarians, these critters are related to sea anemones and corals, but instead

of settling down as a sessile polyp, they float free in the ocean. Some species,

like the moon jelly pictured here, do swim in a rudimentary way by flexing

their bell. Other species, such as the by-the-wind sailor Velella velella (don’t you love it when scientific names are so

pretty!) or Portugese man o’ war, float on the surface and are pushed about by

the wind. These latter two species aren’t true jellyfish (single organisms with

a row of tentacles around the bell), but actually colonies of many hydroids

specialized for feeding, reproduction, etc. Upside-down jellyfish are cool;

they lie upside-down on the bottom, their tentacles facing up. All jellies use

tentacles with nematocysts to capture prey. Nematocysts are like little

harpoons inside the tentacular tissue; when something brushes against the

tentacle, the nematocysts shoot out into it. With many species, you don’t even

notice this, but with others, such as the Portugese man o’ war, you get a

horrendous sting from the poison injected. And the sting of a few species, such

as the box jellyfish, can be fatal. Jellyfish exhibits are popular in aquariums,

usually in dark tanks with colorful lights illuminating the beautiful

undulations of the creatures.

|

| Upside-down jellyfish laying on the sand |

|

| Banners for the "Jellies" exhibit at the Shedd Aquarium last summer |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)